7 Habits of Highly Effective Innovators

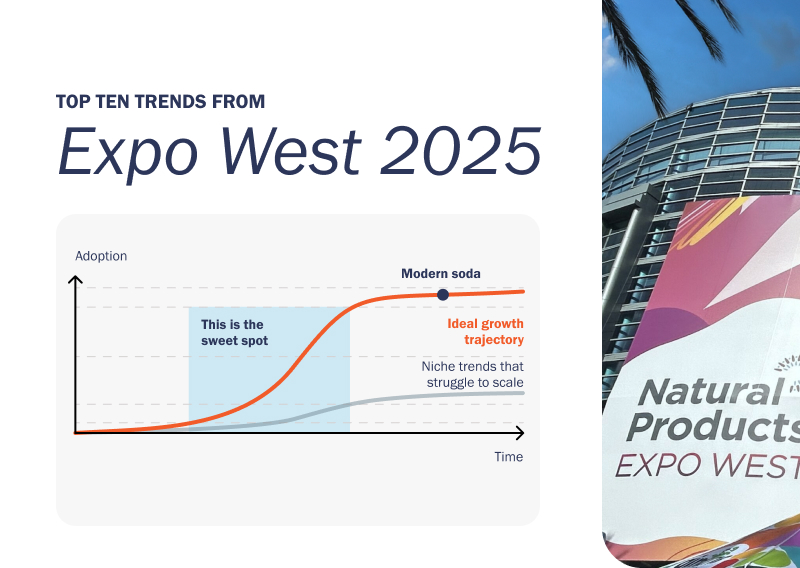

Lately it seems innovation has earned its own 24-hour news cycle.

Corporate earnings reports and mission statements are littered with the term, and it’s perpetually the topic of books, newsletters, blogs, LinkedIn articles, moderated panels and industry conferences. A Google search for CPG innovation returned more than 5.7 million results. And yet, despite the vast amounts of time spent researching, analyzing, and pontificating about innovation, the CPG industry – big CPG, in particular – has a woefully poor track record.

Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen famously estimated that of the more than 30,000 new products introduced every year, 95% of them fail1. A large study of the packaged food industry found that only 25% of new products were still around four years after launch2. By some estimates, as much as $35 billion is spent annually on failed innovation.

What gives?

Plenty of industry veterans have conducted post-mortems on CPG innovation, and most cite some combination of risk aversion, unrealistic goal setting, slow product development cycles, insufficient sales & marketing support, and general bureaucracy. We could add to the list – missing a human insight, over-relying on market intelligence, failing to plan for commercial viability – but in the end it’s easier to point the finger than articulate how to innovate successfully. Over the years Seurat Group has benchmarked hundreds of brands, from emerging challengers to billion-dollar blockbusters. We recently conducted an analysis to identify why certain innovation succeeds and identified seven habits of highly effective innovators.

For many CPG brands, innovation is a foregone conclusion – a templated box on the annual plan – rather than a deliberate strategic choice. But the most successful innovators are those who take a much more purposeful approach. That means starting by clarifying the role of innovation within the company. (Are you trying to increase household penetration? Participate in more “jobs”?) A sharp innovation strategy also articulates a clear financial goal. (Should innovation drive 5% of growth or 50%?) Answers to these questions are of critical importance in driving organizational alignment and decision-making.

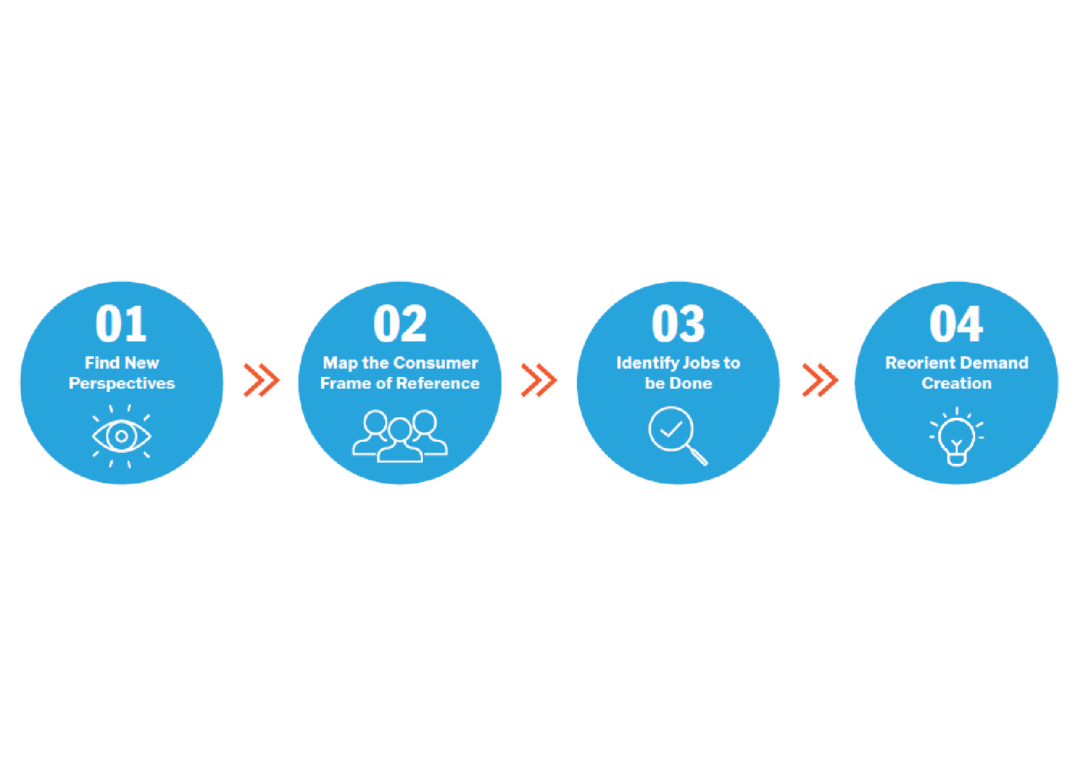

In many cases, innovation is regrettably fueled by capability rather than insight. Product designers and

engineers, eager to pounce on the latest advancements, are all too willing to use some new technology, process and/or capability to justify innovation – often with little regard for the end user. Consider the curved panel TV, debuted with great fanfare in 2013. Samsung, Sony and LG were eager to get in the game, excited by what promised to be a revolution in the viewing experience – only to have it widely panned as a gimmick. Why? Curved panel innovation stemmed from access to a new technology, not user research; the claims about a more immersive experience were simply to post-rationalize and justify an exorbitant price premium. As one ex-Samsung employee put it, “they were borne out of a capability, not a user need.” Similar examples abound in CPG, from product formulations to packaging technology and other novel advancements.

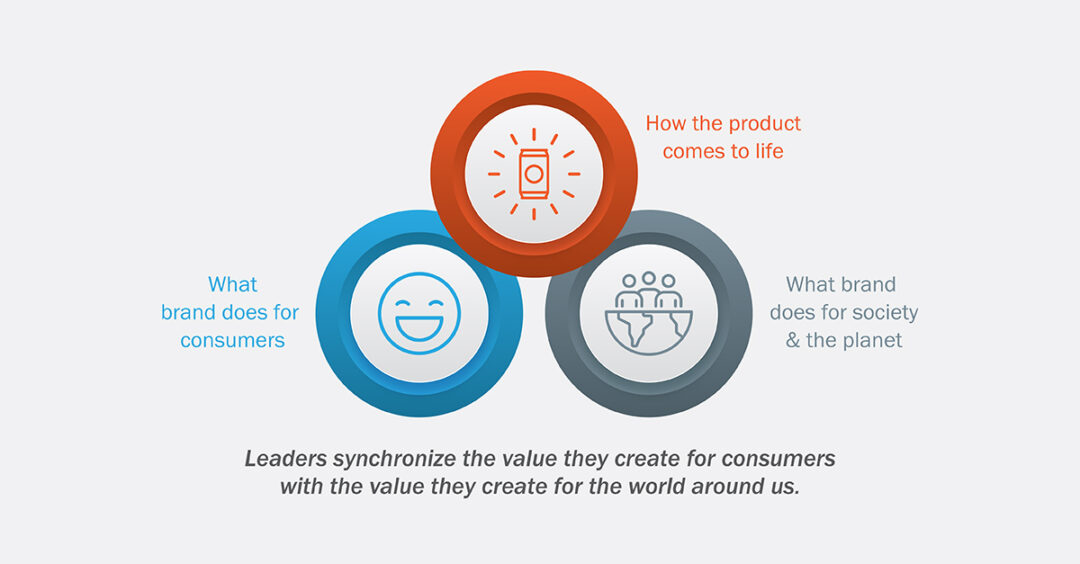

In addition to being strong general managers, the best innovators are experts in consumer behavior. They are not only dialed into the needs of consumers, but also actively evaluating how those needs are evolving to ensure innovation designs for the future, not the past 52 weeks.

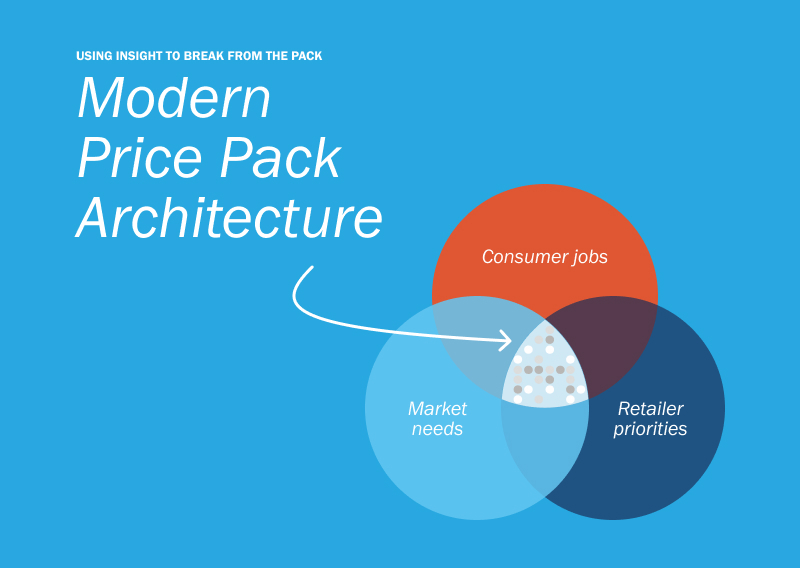

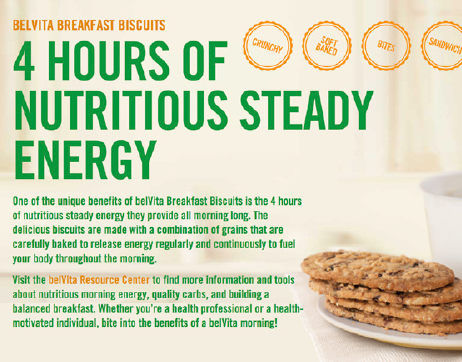

Most new products wind up as line extensions or variants that are different but not necessarily better. By contrast, the most successful innovators recognize the importance of elevating the value equation – in other words, identifying areas where existing products can be improved. While that can occur in the denominator (i.e., providing the same benefit at a lower cost), more often it manifests in the numerator, either through (1) solving pain points or (2) creating delight opportunities. To do this well, innovators identify a clear foil: an incumbent whose value proposition they can meaningfully disrupt and from whom they can source volume.

In 2019, Smucker’s Uncrustables was humming along, a nearly $300MM business4 built on taking the effort out of no-crust PB&J sandwiches for kid lunchboxes and other on-the-go occasions. In 2020, along came Chubby Organics, directly attacking Uncrustables with its nut butter & superfood sandwiches marketed this way: “Chubby Organics offers the same indulgent sandwich experience as the leading PB&J brand, but we swapped out the JUNK ingredients so you can eat our good-for-you sandwiches without the guilt5.” With ingredients like chia seeds, Medjool dates and camu camu, Superfood Sandwiches may not be for everyone – but for those who prioritize a cleaner panel, they represent a significant improvement in the value equation – and enable Chubby to command a ~7x price premium6.

Plenty of brands do the hard work of mining legitimate consumer insights and identifying attractive profit

pools – only to fall down in understanding their right to win. Enticed by the next “bright shiny object,” brand leaders are quick to extend into new spaces without regard for where they can have a unique advantage. Burt’s Bees did a commendable job building equity in natural skin care – and then in 2016, overextended with a fumbled launch into pea protein powder. As one former Clorox leader reflected, “We had built this great equity in natural ingredients, but consumers knew us for skin care, not protein.”

The best innovators scrutinize why consumers choose their brand over others, and where the brand over-delivers relative to alternatives. Thinking this way allows for purposeful exploration of innovation spaces that build upon a brand’s unique right to win.

Several companies have built successful businesses helping manufacturers evaluate new product concepts and gauge “launch readiness.” Unfortunately, in addition to being extremely expensive, these testing methods are limited in that they (1) tend to place outsized weight in stated interest and purchase intent (how many respondents say they are ‘interested’ and/or would ‘probably buy’); (2) lean heavily on historical benchmarks, which can be notoriously inaccurate for new-to-world products; and (3) are highly sensitive to manufacturer-provided inputs (e.g., projected % ACV). By contrast, great innovators take a more holistic – and flexible – approach to evaluating innovation.

Many CPG companies struggle when it comes to commercializing innovation, in part due to what is

frequently a linear, sequential process. In a typical situation, a marketing and/or insights lead partners with an outside agency to commission a study. Results are then presented to marketing, which spins a story and briefs a product development team, which then enlists supply chain, finance, legal and other stakeholders to make the product a reality. At that point, some poor soul is sent off to pitch the idea to sales and obtain a volume forecast. This process leads to inefficiencies and encourages a “CYA” mentality. By contrast, the most successful innovators recognize it takes a village to raise a new product and wire for success by engaging cross-functional stakeholders early and often – and providing ample opportunities for feedback and iteration.

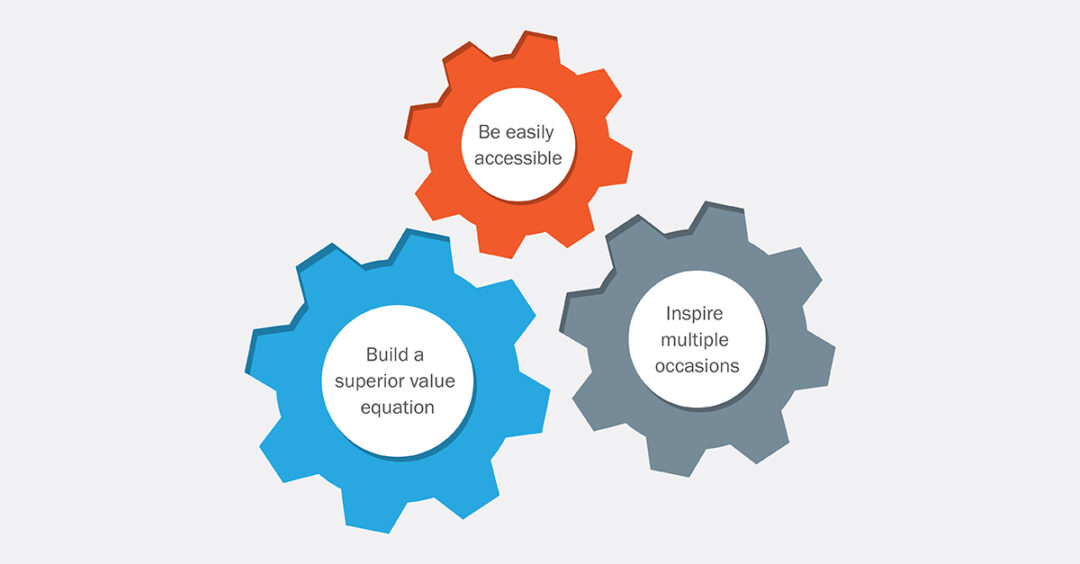

Another common innovation pitfall is relying too much on existing models and capabilities. Big CPG companies spend countless years and dollars building scale and efficiency, ultimately creating perverse incentives to blindly leverage those efficiencies when new models are needed. Consider Campbell’s Sauces, a modern take on the category General Mills pioneered with Hamburger Helper in the 1970s. While the insight territory is rich – consumers want convenient solutions that work with existing tools (skillets, slow cookers) to make dinner easier – Campbell’s lacked the conviction to challenge its go-to-market model, leaving retailers to decide where to shelve the products. Today the bulk of the brand’s website is dedicated to explaining to consumers where to find the items at every major retailer: Microwaveable Meals at Acme, Marinades & Sauces at Giant Eagle, etc.9

By contrast, the sharpest innovators flex the go-to-market model to best suit consumer and customer needs. Think of it as capital ‘I’ vs. little ‘i’ innovation. Examples include:

Licensing: Leading household product licensers capture upwards of 5% of their revenue from licensing and partnership strategies

Direct to Consumer: Blueland, the makers of environmentally sustainable cleaning products, have leveraged a DTC model to enter five household categories within the first 15 months of selling

Community Selling: Leading beauty & personal care brands use consultants and the 1:1 interaction of community selling to recognize virtually overnight success with new products – in stark contrast to the slow and steady model of building awareness and trial in traditional retail channels

Influencer channels: An increasing number of brands are curating breakthrough innovation in authentic channels where target consumers can more easily discover it. Oatly launched first in Intelligentsia coffee, building credibility with baristas and creating awareness among coffee enthusiasts. Similarly, for years RXBAR sold exclusively through CrossFit gyms, rapidly iterating on the product and packaging before finally entering Natural Grocery.

Ready to rethink your approach to strategic innovation? Contact us as info@seuratgroup.com.