5 Ways to Drive Big Brands in the Challenger Age

Introduction

Much has been written about the shift in consumer preferences from older, larger mass-merchandised brands to younger, smaller emerging brands. This shift has captured the attention of brand managers and C-suite executives alike, causing many

large consumer packaged goods (“CPG”) firms to focus on emerging brands within their portfolio—sometimes at the expense of the massive heritage brands upon which their firm’s success was built.

While this shift in consumer preferences merits attention, maturity and size need not be a death knell for big CPG brands. Of the 100 biggest brands in food, drug, mass and convenience, almost 40% saw growth in their most recent year-over-year revenues, with an average gain of 5.5%.1

The most successful big brands have been able to drive consistent financial and brand performance, even in the face of consumer headwinds. Oreo, for example, drove absolute dollar sales growth of 26.9%

from 2011 to 2014, despite its resistance to catering to health or gluten-free trends.2 Managed correctly, big brands can still be an engine for growth for CPG companies for decades to come. For this reason, the Seurat Group’s latest study focused on uncovering what successful big brands do differently to drive lasting growth.

In order to unearth how big, established CPG brands have maintained relevancy and growth, we have distilled learnings from successful and unsuccessful brands alike into OUR BIG BRAND PLAYBOOK, a collection of 5 ways to drive Big Brands in the Challenger Age.

Our Big Brand Playbook

“In matters of principle, stand like a rock; in matters of style, swim with the current.” – Jefferson

“In matters of principle, stand like a rock; in matters of style, swim with the current.” – Jefferson

Successful Big Brand managers understand the delicate balance between being timeless—that is, staying true to their brand’s central value proposition—while also being timely—that is, subtly updating over time to remain fresh and modern. Key to maintaining this balance is a knowledge of a brand’s limitations, and knowing when to say no.

Refocusing brands on their core value propositions has helped several Legacy players return to success. Starbucks was able to bring itself back from the brink by reemphasizing its central value proposition: offering a truly great coffee experience.

Prior to the recession, a memo by Howard Schultz, the company’s then-Chairman, was leaked that described how growth decisions—an increased emphasis on store merchandise and non-coffee sales, the loss of the smell of roasting coffee beans in stores, new coffee machines that blocked consumers’ interactions with their barista—had “led to the watering down of the Starbucks experience.”

Store traffic and sales had already started to slow, and in 2008 the company announced plans to close 600 of its stores—around 10% of its footprint at the time—after the worst quarter in its history as a public company.

In a massive turnaround, the company focused solely on the coffee experience, divesting itself from noncore activities like book and music sales and investing in barista training.

As a result of this renewed focus on the customer experience, Starbucks saw sales increase 10% in the year following the store closures.

Since the company’s realignment around its coffee experience, performance has remained robust; as of 2015, the company had seen a 22-quarter run of same store sales growth above 5% that continually drove its stock to new all-time highs.

Similarly, for Lego, the Denmark-based toy manufacturer, deemphasizing its core product, the brick, in favor of on-trend but brand-off extensions like wristwatches, publishing, and lifestyle products had put the brand under extreme duress in the early 2000s. Believing its core product to be out of date, the company had practiced a strategy of ‘deemphasizing the brick’ throughout the 1990s; in 2003 and 2004, the brand lost 2.5 billion Kroner.7

Faced with near-bankruptcy, the brand focused entirely on its brand heritage, which it embodied in its new mission statement: to inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow.

The brand moved quickly to shed its noncore activities and to funnel its innovation into its core product line. By focusing entirely on the brick, Lego was able to satisfy its core consumer, and in 2014 the brand posted record sales ($4.5B).

Instead of looking to other marketers or industry trends, managers of successful Big Brands are those who use their core consumers to originate new innovation and product lines. Instead of fearing cannibalization, they embrace new consumer occasions that fit into their brand’s central value proposition.

Gatorade, for example, has used its core consumer target — high-performance athletes — as a continual source of insights for innovation. In developing its G Series, a new line of sports performance products, Gatorade and its scientists solicited feedback from more than 10,000 athletes and collaborated closely with high-performance professionals like Usain Bolt, Serena Williams, and Peyton Manning to develop a line of products that would support improved performance before, during, and after a workout, practice, or competition.

Similarly, Lay’s now-annual Do Us a Flavor campaign enlists thousands of consumers’ suggestions every year in order to come up with the potato chip’s next new flavor.

In 2014, the U.S. competition received more than 14 million votes from interested consumers.9 Executives have credited the campaign’s success to letting consumers take ownership through the creation of their new flavor and sharing their preferences online. “The days of focus groups—it’s over,” said Ann Mukherjee, president of PepsiCo’s global snacks group and global insights division at a recent presentation at Wharton. “It’s really about observing behavior.”

As a result of allowing consumers to directly inform its innovation, Lay’s yearly sales rose 14% after the campaign’s first deployment.10 The continuation of this campaign has actively contributed to Lay’s 12.7% absolute dollar sales growth from 2011-2014, placing it among the top performing big, established brands.

In an increasingly crowded consumer, media, and retail landscape, Big Brands must be pervasive in order to capture share of mind. In order to achieve this preemptive presence, they leverage key retailers to gain priority in distribution and display.

Nestle’s Coffee-Mate, for example, has driven brand growth by driving outsized share-of-mind during the holiday season. The brand takes care to launch its annual holiday flavors, such as Gingerbread and Pumpkin Spice, with a high level of customer support intended to capture valuable display opportunities.

By enabling an on-the-ground merchandising team to help keep the shelf tidy during the hectic holiday season, the brand is able to provide a valuable service that retail partners appreciate.

The endcaps and special holiday display sets that the brand is able to capture as a result play a large role in driving sales. This strategy, which the brand has employed for nearly a decade, has helped drive category success even in the face of movements towards plant-based milk alternatives.

Heinz, similarly, uses its strength in foodservice to help establish its positioning as America’s Favorite Ketchup. In addition to its retail business, the brand maintains a strong presence in foodservice where it uses its prowess in packaging innovation and flexibility to help test new flavors while gaining consumer share of mind.

For example, its recent spicy ketchup flavors, Sriracha and Jalapeno, were first released in foodservice in order to cater to a growing Millennial desire for hot condiments. By influencing consumers when they are inclined to try new flavors, the brand then has a greater opportunity to drive trial at retail, where these flavors were later.

In order to resist commoditization, successful Big Brands forsake degrading their product. Instead, they challenge themselves to compete on product quality with an aspirational consideration set of competitors for their consumer’s dollars.

Victoria’s Secret, for example, has maintained its primacy in the lingerie specialty retail market by continually holding itself to a set of aspirational peers. “We are concerned with niche players, like Myla, Cosabella, La Perla, and Agent Provocateur,” said Hadley Hatch, a brand strategy manager. By looking to these luxury players for trends and innovation, Victoria’s Secret can assess which niche trend is worth bringing into the mainstream market. While these High Street competitors sell at a very high premium — Victoria’s Secret’s average bra retails for approximately $30, while Agent Provocateur charges up to $1,100 — Victoria’s Secret has been able to drive impressive sales growth by using its peers’ successes and failures to drive their innovation. As a result, Victoria’s Secret sales were up 6% in the most recent fiscal year.

But considerations need not be against luxury peers in order to drive true competitiveness on quality—they just need to drive consumer preference across a broad array of products that can fulfill their consumption occasion.

As one prior marketer for Slim Jim, a leader in meat snacks, told us, “the consumer’s comparison set isn’t Jack Links – it’s snacking in convenience stores.” Products need to compete not merely with their closest brand or private label competitor but with all the products that compete for that consumer’s attention during the meal, snacking, or consumption occasion.

By striving to compete not just with products within the meat snacks category but with the broader product set available within this channel, Slim Jim has driven robust sales growth of 13.2% for the 52 weeks ending in September 2015.

No business lasts without sustained and holistic investment. In order to see Big Brands thrive in the long term, successful managers prioritize the brands they want to last even when confronting changes in market sentiment and continue to invest in marketing across multiple platforms.

While many Big Brands with mass positioning pour their funds into promotions to win short-term sales bumps, successful players continue to invest in brand-building activity for the long term.

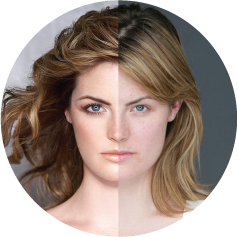

Throughout its sixty-year history, Unilever’s Dove personal care brand has exhibited a concerted investment across a wide variety of marketing vehicles. Since 2004, its Campaign for Real Beauty has leveraged advertisements, videos, workshops, and events to provoke discussion and encourage debate around society’s definition of beauty.15 While seemingly tendentiously linked to sales of bar soap, the brand has nearly doubled in size since the campaign was inaugurated, growing to $4B in sales in 2014 from $2.5B in 2004.

Dove’s long-running Campaign for Real Beauty shows the brand’s commitment to continued support.

Similarly, P&G was able to revitalize the aging, dated Old Spice brand through thoughtful marketing and investment in brand equity. When P&G bought Old Spice, the brand’s then sixty-year-old positioning had caused sales and market share to dwindle.

But instead of optimizing the brand and selling it to the cheapest bidder, P&G invested in marketing and brand-building strategies necessary to target a new audience –Millennial women shopping for their partners. In 2010, the success of its campaign, “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like,” was a runaway success that drove a year-on-year 125% increase in sales.

Conclusion

Big Brands are more than just cash cows. With Big Brands still representing at least 70% of the top 5 CPG firms’ sales, managing these brands to maintain long-term relevancy and growth can reward CPG firms for years to come. But with emerging threats on the horizon, traditional brand marketing is necessary, but not sufficient, to guarantee Big Brands’ success.

Are your Big Brands set up for long-term success? The Seurat Group is a leader in using insights to drive Big Brand success in the Challenger Age. For more on the success drivers to harness today to ensure the future of your Big Brands, contact the Seurat Group (info@seuratgroup.com).