You’re Not in the Category You Think

Why the boundaries you’ve drawn around your business are holding you back.

There are two questions every business must ask: (1) what is my category? and (2) how do I grow it?

After all, brand growth hinges on category growth. (Some eke out modest growth through share gains, but leaders in declining categories struggle to meaningfully grow sales.) While the most successful companies have a category vision that answers these questions, most businesses don’t. This paper explores how to create a winning growth vision by shifting from category as industry artifact to category as consumer reality.

Defining and growing your category starts with understanding the real competition for consumers’ attention and dollars. Recently, we asked executives at a leading frozen pizza company a simple question: Who are your competitors?

Their answer came quickly and confidently. DiGiorno. Tombstone. Red Baron. They rattled off market share data, tracked promotional calendars, and benchmarked against every SKU in the freezer aisle. They knew their category cold—literally.

Then we asked their consumers the same question, framed differently: When you decided not to buy frozen pizza last Tuesday, what did you do instead?

The answers were revealing. Some ordered Domino’s delivery. Others grabbed rotisserie chicken from the supermarket deli. One parent’s teens made nachos and called it dinner.

When you define your category too narrowly, you optimize for a game consumers aren’t playing. You win battles for share within artificial boundaries while missing the larger war for relevance in their lives.

When companies adopt a consumer lens, they typically discover a market three to five times larger than the one they thought they were competing in—and with it, a different set of growth possibilities beyond those defined by product alone. This has inspired many to hire consultancies and research firms to create “demand spaces.”

Unfortunately, these exercises are often too broad, primarily given companies’ desire to cover the entire portfolio (for example, all personal care or beverages). The resulting 30,000-foot view generally lacks enough detail on consumer decision-making to drive change.

For years, the company operated with a clear view of its competitive landscape. They tracked share against other applesauce brands. Benchmarked innovation against what appeared in the fruit puree aisle. By every internal metric, they were winning. And yet, growth had plateaued. The team found themselves fighting for smaller gains, caught in a zero-sum battle over a stagnant category. Line extensions generated modest incrementality at best.

The breakthrough came when the team stopped asking “How do we win in applesauce?” and started asking “What jobs do our products fulfill in consumers’ lives?”

Research revealed something the category lens had obscured. Parents weren’t buying pureed fruit. They were solving a daily problem: What can I put in my kid’s lunchbox that’s convenient, doesn’t require refrigeration, won’t come home uneaten, and doesn’t make me feel like a negligent parent?

That problem—”a better-for-you lunchbox snack kids love and parents feel good about”—was the real competitive arena. And in that arena, the brand was competing against granola bars, string cheese, fruit snacks, mandarins and whatever else parents reached for during the nightly lunchbox packing ritual.

“Parents weren’t buying pureed fruit. They were solving a daily problem.”

The reframe changed everything. The brand reimagined its comms strategy and launched a line of puddings in the same squeezable pouch format. Once they drew new lines around their category—lines that reflected how real decisions get made in kitchens and pantries—they found room to grow that had been invisible all along.

A fast-growing supplement brand had built its reputation on a flagship cognitive enhancer promising sharper focus, improved memory, and faster reaction time. Within the “cognitive supplement” category, they were a clear leader.

Unfortunately, the cognitive supplement market had ground to a near-halt. The brand could continue fighting for share in a static pond, or it could ask a more fundamental question: What do we ‘do’ for consumers?

Deep qualitative research with devoted users revealed a profile that defied the “brain health” positioning. These were biohackers. People who tracked their sleep with wearables, experimented with cold plunges and red light therapy, timed their caffeine intake to circadian rhythms, and viewed their bodies as complex systems to be tuned and refined.

For these consumers, the cognitive supplement was one node in an interconnected web of interventions designed to improve mind and body performance. This insight recast the brand’s strategic situation. The available market wasn’t brain health; it was the vast and growing universe of human optimization, with levers like energy, recovery, sleep, gut health and stress resilience.

The brand responded with a fundamental expansion of its positioning and portfolio. Marketing shifted from cognitive benefits to the broader promise of optimization. Product development accelerated into adjacent need states.

“The available market wasn’t brain health; it was the vast and growing universe of human optimization.”

What’s particularly instructive about this example is how the insight emerged. The category data told one story: a maturing market with limited upside. The consumer lens told a completely different one: a passionate, growing tribe of optimizers with virtually no ceiling on their willingness to invest in themselves.

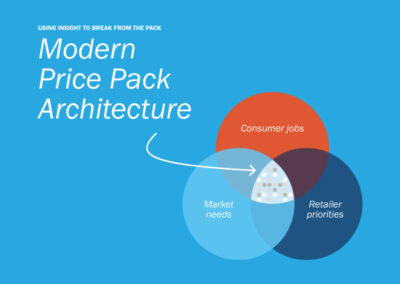

From Insight to Action:

Redefining Your Category Through the Consumer’s Eyes

The above examples highlight a common gap. The category these companies thought they were competing in existed in retail aisles, syndicated data and spreadsheets. The category that mattered existed in the minds of consumers making real decisions in real moments.

How, then, can businesses move from a commercially defined category to one inspired by consumer jobs? The answer lies in human empathy and business creativity.

Most category research focuses on the middle of the bell curve: representative users, average purchase occasions, typical consumption patterns. While this makes intuitive sense, it systematically obscures insights that matter most for growth.

- New entrants reveal what initially attracts users. What problem were they trying to solve? Which alternatives did they consider, and what tipped them in? These consumers speak in jobs, needs and moments—the language of demand.

- Heavy users expose the full breadth of what your category can do. They’ve discovered occasions and applications occasional users never imagine. They’ve pushed boundaries and highlight not what is, but rather what can be.

- Lapsed users illuminate category limitations and vulnerabilities. Understanding why they left reveals where your category fails to deliver—and often, where a competitor or substitute has quietly taken over the job.

Spending time with these consumers builds the empathy required to see your category as they see it: not as a shelf set or a competitive frame, but as one possible solution to a problem they’re actively trying to solve.

Once you understand the job(s) your category fulfills, the next question is, Who else is doing that job? This is where the frame of reference expands—often dramatically.

Mapping this broader competitive set – typically through ethnography and longitudinal journaling – is where strategic opportunity lives. When you see who else is solving the same problem, you notice gaps. Places where existing solutions fall short. Tensions that go unaddressed. “Hacks” consumers employ. These are the seeds of growth, pointing to solutions that would seem nonsensical within the narrow category definition but are perfectly logical within the consumer’s frame of reference.

Demand maps are a useful starting point for decomposing consumer needs or jobs. However, these frequently lack sufficient detail on what drives decision-making, whether that’s in the omnichannel shopping environment or surrounding moments of consumption. Best practice is to drill deep into each consumer need and build a multi-dimensional profile: underlying functional and emotional drivers, priority attributes that shape choice, existing solutions that compete for the occasion, tensions that remain unresolved, and growth opportunities that emerge from addressing these tensions better than anyone else. This exercise then culminates in a pointed job-to-be-done statement: get [target consumer] to [desired behavior] by [proprietary way in].

Analyzing jobs this way reveals whitespace opportunities where your brand has a differential right to win.

If the first three steps reveal where growth lies, the final step is about capturing it.

Too often, the response to new strategic insight is a new product. But when you’ve redefined your category through the consumer’s eyes, opportunities emerge across every dimension of how you go to market. A consumer-defined category might reveal that your product already solves the job admirably; the problem is you’re not showing up in the right places, your value equation is off, or your messaging speaks to a Circana category rather than a consumer frame of reference.

Demand creation spans the full spectrum: innovation, certainly, but also penetrating more relevant channels, exploring alternative ways to celebrate value beyond price, and revisiting how you show up in consumer-facing communication. Redefining your category should reorient all these efforts toward a single objective—delighting consumers within the frame of reference they recognize. When every lever pulls in the same direction, growth compounds in ways that narrow category thinking never allows.

Answering the Two Questions

We began this paper with two questions every brand must answer: What is my category? How do I grow it?

The conventional approach answers both from the inside out—starting with the product, the shelf set, the competitive frame defined by industry convention. It leads to incremental thinking, zero-sum battles, and growth ceilings that feel inevitable.

The consumer-defined approach inverts the process. And in doing so, it typically reveals a market far larger than the one you thought you were competing in—and a set of growth pathways that were invisible from inside the artificial boundaries.

The boundaries you’ve drawn around your business are probably holding you back.

It might be time to redraw them.

Let’s discuss: info@seuratgroup.com